According to the AP (through the NY Times), Sharman Networks, the makers of the Kazaa file sharing program, have reached a deal to settle its piracy lawsuits with the music and movie industries. Sharman Networks's Kazaa (and the FastTrack network it runs on) has been on the world's major peer-to-peer (P2P) networks in the post-Napster period. Although Kazaa did not catch on immediately after Napster was shut down, it was its first major successor. Sharman Network used to brag that over 350 million copies of its Kazaa software had been downloaded, but that claim is no longer on its webpage. Although not as popular as it once was, the FastTrack network is still one of the world's largest. (See slyck.com's daily listing of the number of useres on the top P2P networks.)

Sharman will pay $115 million to music labels and movie studies as a result of the settlement, and has also agreed to try and stop the proliferation of copyrighted music and movies using its programs. This, though, is likely a meaningless condition because the thing that has allowed Kazaa to be active for so longer after Napster was shut down is the fact that it is a decentralized P2P network. This means that the FastTrack network protocol is out there, and Sharman can't simply shut it down, or control it directly. If users want to use other FastTrack clients to "share" and to download files, nothing is stopping them.

It's possible that Sharman has agreed to play an active policing role, though this is not stated in the article. They could, conceivably, monitor the data transmissions on the network and then attempt to corrupt that data in ways that would make the experience of trying to download materials using FastTrack slow and annoying. This, of course, would likely annoy and drive away its users, which would severely harm the plan of transitioning to a legal service.

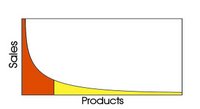

Of course, ultimately this does not matter at all for file sharing. The RIAA and MPAA are just chasing a white rabbit here by going after the companies that started these networks. The networks can be used without the founder’s software (unlike Napster), but even more importantly, new and better networks will just pop up to replace them (like after Napster was closed and Kazaa came onto the scene). They will never catch the rabbit. The only was to stop (or limit) piracy is to compete with P2P networks and win away users. That means providing legitimate services with a full catalog of available titles at a reasonable price. It needn’t be free; it only needs to compete with “free”. Until that time, there will always be an enterprising software engineer out there willing to provide a better network to hordes of users who want one. The RIAA and MPAA seem to be trying to turn back the clock to a world where this technology is not out there; that can’t happen. They need to accept the fact that the conditions that led to the profits they earned in the mid-90s are gone, and adapt. Doing so can lead to offerings from the industries that win consumers away from file sharing, improve profits for the industry, and provide a better experience for users.

I should also point out that the industry’s strategy of suing its users en masse every so often also seems to be fruitless. While the program seemed to work at first (it initially made a significant dent in the number of users on P2P networks), it seems to have no chance of eliminating piracy, as file sharing networks are much larger than ever. For whatever reason, users have not been scared away.

Maybe if the RIAA/MPAA would offer a useful alternative to consumers, they would be able to increase profits while simultaneously winning users away from P2P. Scaring them has not worked; instead try enticing them way with a better system. The nice thing about P2P architecture (from an industry point-of-view) is that if you remove the users, the content is taken away as well. If they can just offer a carrot instead of a stick, that white rabbit just might come to them.